- Home

- Raving Beauties

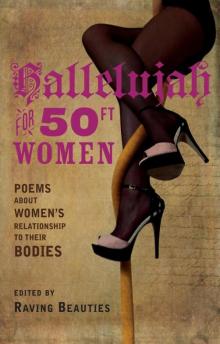

Hallelujah for 50ft Women Page 2

Hallelujah for 50ft Women Read online

Page 2

The receptionist is indifferent; he’s seen it all,

leads her through labyrinthine corridors to a plain white room.

The director looks her up and down; tells her to undress.

In an alley among whores, drunks and the stench of fish,

the Dutch merchant strikes a bargain with an American captain,

who has to sell his ship. Years later, broke, he sells the mermaid

for a fraction of what he paid. But that’s the way with sirens,

bestowing fortune or grief as whim dictates.

Bathed in his laptop’s subaqueous glow,

a man wanders the internet’s dark alleys, safe search off.

He finds a video of a girl with buoyant breasts

and hairless sex sprawled on the bed

of a white hotel room. He clicks.

The posters appear overnight: a genuine mermaid,

caught off the shores of distant ‘Feejee’. Crowds surge

to the museum, pay their dime. The men go to catch a glimpse

of milky skin, flowing hair, peeping nipples;

the women to hear the songs she must surely sing.

She dies several times a day; fakes so many little deaths

she’s starting to feel a part of her has died inside.

By now she doesn’t have to think: just curls her lips,

and, eyes glassy, looks at the wave-like patterns on the ceiling

while her co-star fills the red-pink shell of her sex.

Munching popcorn and cotton candy, the punters

walk past waxworks of famous murderers, but still are not prepared

for the sight of a blackened baby orang-utan with a salmon tail.

The Feejee Mermaid sprawls in its case,

glass eyes reflecting all those drowned expressions,

lips curled as though in laughter at some secret joke.

ALEX TOMS

Her Mother Hides in the Wardrobe

Julia wears a pink dress and earrings,

has green eyes and a pony tail.

She has herpes, hepatitis, thrush,

staphylococcus, cervical erosion, HIV.

She lives with her mum and dad in

a studio flat in an old district of Kiev.

They have three cats: Hanka, Efedra,

Morifius – opium, ephedrine, morphine.

She learns English before Euro 2012;

‘my name is Julia, fifty dollars fifty minutes’.

BOGUSIA WARDEIN

Katie’s end of week routine

Ah step, tenderly

into a small ocean.

Lower each inch

of skin

in nobody’s eyes.

A layer of lavender

bubbles. No need

for acting

ah let ma belly hang

its childbearin’

rounded pear shape.

Drop ma whole body

in. Caressed by heat

of the water. Protected,

enveloped, like a baby

in its mother’s womb

listening to the rhythm

of ma heartbeat as ah once

did hers. Ah submerge

ma head, float

until ah surface,

gaspin’ for breath.

Washin’ their hands,

their eyes away

from memory.

Emerge skin pink,

soft, fresh as

a newborn.

JULIE EDGELL

Three Ways of Recovering a Body

By chance I was alone in my bed the morning

I woke to find my body had gone.

It had been coming. I’d cut off my hair in sections

so each of you would have something to remember,

then my nails worked loose from their beds

of oystery flesh. Who was it got them?

One night I slipped out of my skin. It lolloped

hooked to my heels, hurting. I had to spray on

more scent so you could find me in the dark,

I was going so fast. One of you begged for my ears

because you could hear the sea in them.

First I planned to steal myself back. I was a mist

on thighs, belly and hips. I’d slept with so many men.

I was with you in the ash-haunted stations of Poland,

I was with you on that grey plaza in Berlin

while you wolfed three doughnuts without stopping,

thinking yourself alone. Soon I recovered my lips

by waiting behind the mirror while you shaved.

You pouted. I peeled away kisses like wax

no longer warm to the touch. Then I flew off.

Next I decided to become a virgin. Without a body

it was easy to make up a new story. In seven years

every invisible cell would be renewed

and none of them would have touched any of you.

I went to a cold lake, to a grey-lichened island,

I was gold in the wallet of the water.

I was known to the inhabitants, who were in love

with the coveted whisper of my virginity:

all too soon they were bringing me coffee and perfume,

cash under stones. I could really do something for them.

Thirdly I tried marriage to a good husband

who knew my past but forgave it. I believed in the power

of his penis to smoke out all those men

so that bit by bit my body service would resume,

although for a while I’d be the one woman in the world

who was only present in the smile of her vagina.

He stroked the air where I might have been.

I turned to the mirror and saw mist gather

as if someone lived in the glass. Recovering

I breathed to myself, ‘Hold on! I’m coming.’

HELEN DUNMORE

Grandmother

My Grandmother’s shoes are laced-up tight

beneath her dress of stretched violet.

Her jars of beans are counted and polished,

her starched, bleached sheets hung out to dry.

Streuth, girl, she says, when a man beats you

it’s with the beam of love in his eye.

I’ll choose for you a man made of meat –

if he feeds you, he’ll feed you the best cuts of the beast.

Here come the men like a full river,

here the men come like a rope, thrown.

They bring their gifts of broken-legged horses,

ready-made cigarettes and pressure pans.

They talk to Grandmother in her breathless kitchen,

as she skims the cream or stirs the tub.

They talk to Grandmother in the ticking parlour

where she rocks and rocks a creaking pram.

If they put their knuckles or flesh against me,

I’ll kick the parlour chairs, I’ll break their hands.

You can shut me up in the oasthouse, Grandmother,

my neck will be snow-smirred, scalded with ice.

I may be gloved and small-footed, Grandma,

I may seem, in my black dress, all shy of the plough;

but my empty bowl gleams like a chosen thing

and my heart, Grandma, my heart is a field.

SUZANNE BATTY

Ventriloquist

In life your anger never burned in words,

You turned away and whispered as you went

To clean or cook; that sibilance we heard

As if from some small dying creature sent.

You spoke in polished ornaments and flowers

Arranged in vases, pastry made for pies,

In floors scrubbed clean and whites you boiled for hours.

One morning woke and knew that these were lies.

In search of truth wherever it might be,

You followed all those unsaid words you’d throw

n

Down to the beach, and straight into the sea,

Your apron on, its pockets full of stone.

Looking for you, feet sinking in the sands,

I see white death with fish held in her hands.

RUTH AYLETT

Bright Day

(i.m. my mother)

There is a sea of people

in the church. The ceilings are high.

I have made the long walk

to the golden railings on my spindly legs

in my white Communion shoes and socks.

The crowd pushes to the big swing doors.

Outside it’s a bright, bright day.

The white sun flashes at me and I want

to fall, the cough I was keeping

at the back of my throat starts to bark.

My mother looks at me, at my white face,

at the black rings circling my eyes.

She has a question on her face.

She stretches out her arm, her hand

cups my elbow, her other hand clasps

my wrist – helping me across the road.

The sun’s daggers are flicking

at cars as they pass. My spiky elbow

rests in my mother’s cupped hand

in the soft pads. Her roly-poly fingers

press through the nylon of my white

summer cardigan, the elbow folds

into the blanket of her hand.

From elbow to wrist, she holds the long bone,

carries it across the road.

MARY NOONAN

Armour

This body

Is no more than the armour

That an archangel

Chose to wear to pass through the world

And, disguised like this,

With its wings wrapped up

Inside of me,

With the visor of its smile

Hermetically sealed on my face,

It goes into the heat of battle,

Is assaulted by injury and insult,

Soiled by vicious looks

And even caressed

On the steel plating of its skin

Beneath which revulsion incubates

An exterminating angel.

ANA BLANDIANA

translated from the Romanian by Paul Scott Derrick & Viorica Patea

If

If my body was a country, it would be

Afghanistan; pregnant with IEDs, problematic, incomprehensible;

If my body was a river it would be

Indonesian Citarum; sluggish, mercury poisoned, cargo of turds and plastic;

If my body was an animal it would be

A hyena; toothless, starving, drooling in its concrete lair;

If my body was a colour it would be

That indefinable, infantile impasto of all colours mashed together;

If my body was music it would be

Jangling, angry discords best switched off;

If my body was a woman it would not be

Me.

FRANCES KAY

Nude

(after a portrait by Dominique Renson)

Framed by white wood, a woman stands,

thighs swathed purple, muddied plum,

thick, flexed and worked,

textured to a dense auburn tuft,

resinous between rounded hips.

Square-knuckled fingers

hang limp, curled and shadowy,

familiar in their empty tenderness.

Whereas the stomach’s smoothly oiled

pink is smeared in a rich beige tallow,

laboured over, brushed

to where lilac ribs corrugate,

without any mark or mole.

Uneven, light-bulb breasts

illuminate different directions,

capped by nipples daubed peach

soft shading, as if sucked slowly.

And higher, the throat

is ridged by another redbrown thicket,

brushed back from the face

where all movement culminates.

With its dark lips, jutting cheeks,

flared nose and still, clear examination

of the eyes, blue – mine staring back at me.

SARAH HYMAS

I put a pen in my cunt once

I put a pen in my cunt once

just to play with myself

when I was at a loose end

when we were in one of those times

lying in straight lines in the dark

not touching

long milk hands stroke

my words to sour cream

this is what it wrote

DEBORAH ALMA

On New Year’s Eve

It’s that dangerous lust feeling, that tonight

why not just let go? thing and you reach

for the red lipstick, that colour

your mother wouldn’t let you

wear as a teenager,

the red of blood dripping

from vampires’ teeth,

chilli pepper red hot red,

the kind of red that pouts

and swings its hips;

and there is a frizz in the air

a stirring, a throbbing

dance that enters through your feet and you think

what the hell, and your shoes

match the lipstick, and oh baby

you are so ready,

and when he turns and smiles

all you can think of is cock

and the two of you

in a darkened corner thrusting tongues

and you know

you are going to hate yourself in the morning,

but you have another tequila anyway,

and you slip your hand into his

but only because you like the curve of his arm,

and you may not remember his name in the morning

but right now he’s perfect,

and you think what the hell,

you are so ready,

oh yes baby.

KERRY HAMMERTON

He Sees Me

I like this man who

charmed by me

slips alongside and inside of me

like the tongue of a dog

lapping at my life

throwing the ball of it

into the air with joy

to catch me out again and again

and laugh at my earnestness in odd places

he says

he says I rise up like a hundred balloons

let loose from a child’s hand

beautiful, bold, even when out of sight

like notes of music falling over themselves

like larks ascending

he says when I sleep I sigh

and he watches me wake and smiles

at the fuzz of my hair and my mind in the morning

he is charmed, he is charmed

I begin to charm even myself

he sees me so lovely

DEBORAH ALMA

Bulimic

Blood dries on the bathroom floor

beside my head as I lie curled in

a foetal ball watching dripping pipes.

I am a dirty puddle of darkness after purging.

In black clothes on a bed of polar tiles

my back yawns bare between a belted waist

and little top, silently awing the still tub.

The dim moon of my body is shocked

by pale shores of arms and neck and face,

made paler still by moonlight and stars.

At midnight the bathroom is hushed.

Ingrained in the circle of my dead gaze

the toilet stops hissing. Innocent

as a lunatic I knelt hours ago before it,

hearing a skinny saint rave within me –

‘Empty, empty her and she’ll be thin!’

I clung to the covenant like clingfilm

over a rib and heaved her hungers.

Drunk on her breath and bowed

to a cistern I emptied, emptied,

emptied her,

burned her weeds and wiles –

I trespassed into the body’s chambers

and raped it with two blistering fingers.

This fire may lick and melt

but it is unforgiving; my fingers

may enter but parch and scorch

in the caustic passion of juices from the gut.

The body weeps, reluctant.

Be wary of it.

She erupts maniacally

until blood makes her holy, barren, empty.

Neither tears nor the easy flush

can patch a ceremony. It escapes

into the eve of thinness.

The cold body keels in honeyed drips

onto tiles; knees collapse,

elbows dance graceless

from the seat; a demented head

falls on a scale, blood trickling from the nose.

Now, curled beside dripping pipes,

weighing the head’s load, in black clothes

framing the arms, the neck, the face.

The tiles do not warm the numb.

We move like spirits.

LEANNE O’SULLIVAN

Underneath Our Skirts

Although a temple

to honour one man’s voluntary death,

Hallelujah for 50ft Women

Hallelujah for 50ft Women